NEWS

&

Musings

Phenological Phacts and Photos with Carl Martland / February 2026

Birdseye Views

Phenology – “a branch of science concerned with the relationship between climate and periodic biological phenomena (as the migration of birds or the flowering and fruiting of plants).”

The Eyes Have It

My friend Tony, whom I have frequently mentioned in these essays, is a far more avid birdwatcher than I am. He travels to distant countries to add to his life list. I am happy to get a particularly nice close-up of a red breasted nuthatch. He saves at most one in ten of his 25-megabyte photos, while I save almost everything. His photos, on the average, will naturally be superior to mine, but my photos, well-named and well-organized, provide a more useful data base. However, we both agree that a good photo of a bird must show the eye. And that is why, in this essay, the eyes have it.

In February, the snow is deep, the nights are beyond cold, we stay close to the wood stove, and we’re careful to fill up the bird feeders. These feeders aren’t just for the birds, they’re for us. We have our feeder located about twenty feet from a large window in our kitchen. I sit at the counter, eating breakfast, watching the birds fly back and forth between the feeder and the nearby trees. I continue enjoying the avian activity as I do the dishes, and finally, I lay a fire in the wood stove. My chores completed, I reluctantly head to my office to do something useful, like paying the bills or working on my taxes. But every hour or so, throughout the daylight hours, I take another look at the feeder. Will the juncos finally show up? Will there be robins in the big maple trees? Will a flock of goldfinches be there? Will I have another view of birds’ eyes?

So, that is what this essay is about. The birdseye views that I get through our kitchen window. All of the photos in this essay were taken through that window. I have nothing against those who go on nature tours in Costa Rica, but I’m happy to stay at home, in our kitchen, binoculars and camera next to my cereal bowl, hoping for a surprise – a pair of cardinals, the first brilliant male purple finch of the year, or the first little flock of redpolls in several years. Or the surprise that took place just a half hour ago as I sat down to polish off this essay. What was that? You’ll see.

Chickadees

Chickadees apparently know every location where anyone has ever put out a feeder. When we first put out a feeder in the fall, the chickadees take only an hour or two to notice that the restaurant is open. When we put our feeder out after returning from a long absence, it is always the chickadees who show up first. They then alert their allies, little friendly birds with similar black and white garments, including titmice and nuthatches.

March 13, 2022

A chickadee has a seed in its beak. What’s next? Another seed, or perhaps a bite of suet?

Each bird has its own characteristic approach to the birdfeeder. Redpolls come in flocks, sometimes a dozen or more at a time, and they will all try to crowd onto the feeder, but, since there is too little room, some will forage below. These birds, along with finches, will remain on or below the feeder for a minute or more at a time. Chickadees, like Zorro, get in, make their Z, and get out to the comfort and safety of a nearby tree.

February 5, 2015, 16 degrees, partly cloudy……. Chickadees, whose flocks number only a half dozen, spend only a second or two at the feeder, just enough time to grab a sunflower seed. They then fly away, bouncing, to the cedar by the back door, the big willow, the spruces, or the maples – usually in a different direction than they came from.

Finches

House finches and purple finches are welcome guests at the feeder, because the males in mating season are happy to show off their glorious colors. This year, a half dozen or so female purple finches have been regular visitors, but I have only seen a couple of the males. However, even one glimpse of a brilliant male is an adventure.

February 5, 2022

Sunny but cold, 15 degrees and windy after another foot of snow fell overnight. Was it a coincidence that the first-time visitors to the feeder included four purple finches, three goldfinches, a nuthatch and a dove!

Goldfinches come to the feeder as the males are just beginning to show the colors that inspired their common name. In February and march, we can see the yellows first becoming visible, then becoming plentiful, and finally becoming triumphant. Even their subtle colors of mid-February are beautiful.

February 14, 2016

A goldfinch is just starting to show its colors.

The day after taking the above photo turned out to be one of the coldest of the past 25 years. The cold did not deter the finches:

February 15, 2016, minus 14 at 9am. The best group of finches we have yet seen gathered today at the feeder. A dozen goldfinches, a dozen purple finches, plus a couple of chickadees and a white-breasted nuthatch. I managed a photo showing 26 birds on and around the feeder. Yesterday was the coldest day of the winter (minus 21 in the morning; high of minus 4), so I wondered if the large assemblage of small birds was related to the cold. But maybe they came here because some of the usual, nearby feeders were empty.

Blue Jays

Blue Jays arrive at the feeder early in the morning, and they drop by now and then throughout the day, perhaps alone or with one or two of their pals. Their size tends to scare off the small birds, and they hold their ground when the red squirrels pop up out of their tunnels through the snow.

March 7, 2018

A blue jay has picked up one of the small, spherical seeds that has fallen off the feeder. Blue jays forage under the feeder, because they’re too big to get the food from the feeder without undue contortions.

Nuthatches

White-breasted and red-breasted nuthatches are small woodpeckers that frequent the feeder throughout the winter.

March 30, 2022, 26 degrees, 915am

A pair of red-breasted nuthatches spent about ten minutes of surveying the feeder, flying back and forth between the willow and the spruce, never spending more than a few seconds on each perch. Finally, they dared to land on the feeder – but immediately flew off. By their third or fourth try, they finally accepted the safety or simply couldn’t resist the sunflower seeds.

Nuthatches often strike a pose, sometimes with their beak straight up as they take a bite and sometimes seeming to stand on their head as they peck at the suet.

December 8, 2020

A white-breasted nuthatch strikes a typical pose as it eyes its next bite.

Scowling Grosbeak

Three species of grosbeaks can be found in the North Country, albeit not easily. All three have the striking beak that gives them their name. If Jimmy Durante had a favorite songbird, it would likely have been one of the grosbeaks. The rose-breasted grosbeak is aptly named, as I would demonstrate if I had a photo of one at the feeder. However, when I searched my journals, dating back over a quarter century, I found only four references to these colorful birds, all of them in the summer.

June 25, 2000 (hot, hazy and humid, 86 degrees, rain in late afternoon)

I spent an hour and a half birdwatching. The best sighting was a very vocal rose-breasted grosbeak. He warbled from the top of a larch, then was flying around tree tops in the inner meadow. Extremely melodious singer.

The pine grosbeak is even rarer. A half-dozen that visited our feeder in early March back in 2023 are the only ones I have seen. Mr. Sibley’s guidebook indicates that small flocks are often seen in more northern fir and spruce forests. Perhaps the bird was named long ago by someone unsure about the different kinds of evergreens.

That leaves the Evening Grosbeak as the one we are most likely to encounter. Don’t be misled by their name, as they are most apt to be at the feeder before noon. My PPP for February 2022, which was all about grosbeaks, noted that I had seen these birds once or twice a year in the early 2000s, but had only had a few views in the subsequent ten years. I had recently seen a small flock at our feeder, so I held out hope for the future. However, over the next three years, only two small flocks stopped by for short visits, one for a week in early April in 2023 and another for a few days last winter.

This year, we were happy to see a few evening grosbeaks soon after we put out feeders in mid-January. Since then, they have been here every day since, often in groups of a dozen or more.

February 14, 2026. Backyard Winter Bird Watch begins! And the grosbeaks were the first birds at the feeder. Last night, in the draft of my PPP, I wrote that I had seen “as many as 21 at a time.” Today, to my great surprise and pleasure, forty of them gathered in the top of the big maple at the corner of Post Road and Pearl Lake Road.

So now I have many photos and videos of these large, colorful birds. However, I have chosen a photo from 2020 for this essay. Admittedly, grosbeaks are dominated by their beak, but, as is evident in this photo, this bird has an attitude equally worthy of notice. One could say that this character has a wry smile, but I think its expression suggests a better handle for a mis-named bird that I have only seen in the morning or early afternoon. I think this could be the defining photo of what could be called the “Scowling Grosbeak.”

December 16, 2020

“Who you looking at?”

Eyes on the Ground

I try to end each essay with a memorable photo and a clever remark. With my new name of Scowling Grosbeak backed up by what is certainly a memorable photo, I figured my work was done. All that remained was to get a cup of hot tea, enjoy a mid-afternoon snack, and head to my office for a final review of my draft. I took a quick look out the window when I walked into the kitchen, but as usual in late afternoon, no birds were at the feeder. I filled the kettle, waited for the water to boil, prepared a snack, and, when I turned back toward the window, was astonished to see a huge barred owl sitting atop the pole holding up the feeder! I shouted the news to Nancy, grabbed my camera, and rushed to get a photo.

It turns out that I needn’t have rushed. The owl just sat there, slowly turning its head far to the right, then far to the left, sometimes with its eyes on me and sometimes with its eyes on the ground hoping to see the red squirrel emerge from one of its tunnels. After taking plenty of photos and videos and drinking my tea, I went to my office to work on this essay. I took a peek out the window every few minutes to find that the owl, like Poe’s raven, was still there. To paraphrase Poe’s famous finish to The Raven:

And the owl never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting,

on the blackened steel pole, just beyond our kitchen door.

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,

And the sunlight o’er him streaming, throws his shadow ever more.

Photos and text by Carl D. Martland, founding member of ACT, long-time resident of Sugar Hill, and author of Sugar Hill Days: What’s Happening in the Fields, Wetlands, and Forests of a Small New Hampshire Town on the Western Edge of the White Mountain. Quotations from his book and his journals indicate the dates of and the situations depicted in the photos.

Phenological Phacts and Photos with Carl Martland / January 2026

Oak Diversity

Phenology – “a branch of science concerned with the relationship between climate and periodic biological phenomena (as the migration of birds or the flowering and fruiting of plants).”

The Oaks Are Coming

In the North Country, we are close to the northern edge of the range of oak trees. While we find a few oaks along our highways and isolated in the woods, we seldom find a place where we can splash through several inches of oak leaves in a forest dominated by oaks. A couple of years ago, I wrote about finding a couple of hundred northern red oaks in Foss Woods, but only a dozen or two were mature enough to produce acorns, and a majority were less than 30 inches tall. The concluding paragraph of that essay noted that:

I now recognize that the tiny oaks I come across are much more than an inconsequential few of the thousands of small trees found in the woods. They are young pioneers pushing northward, and I am happy whenever I across one, no matter how small. Oaks are not known for their colors or their beauty, but in early spring or late fall, if the sun is right, you may get a chance to take a fine “baby picture” for what will become, long after we’re all gone, a mature grove of northern red oaks.

The final photo of that essay about northern red oaks is reproduced above to introduce this essay on oak diversity. The photo was taken in October 2022 in what I call the Lower 40, and, in my journal, I pondered the northward movement of northern red oaks in response to climate change:

I came across this lovely, tiny oak while walking along one of my trails in the Lower 40.

Will this tree mature as part of a majestic grove of northern red oaks?

I certainly won’t live long enough to find out the answer to this question, but I can perhaps get a glimpse of that future by looking more carefully at what can already be found a little further south.

“Autumn Leaves Must Fall”

Oaks hold on to their leaves much longer than most trees, and these leaves decay very slowly in the crisp autumn air. But, as the song reminds us, “Autumn leaves must fall,” and the oak leaves eventually fall atop a layer of already faded maple and birch leaves.

Last October, we took one of our favorite walks along the boardwalk at the edge of the salt marshes at Great Bay Nature Center in southern New Hampshire. I was happy to find leaves from two species of white oaks that cannot be found in the North Country. All oaks in the white oak family have rounded rather than pointed lobes. The classic white oak typically has five to nine lobes with deep valleys between them. Swamp white oaks have many more, but much tinier lobes.

October 31, 2025: white oak leaves posing on the boardwalk at Great Bay Nature Center (left) and a tiny swamp white oak growing next to the boardwalk.

I was equally happy to find several species of the red oak family in addition to the northern red oak, which was the only species I had ever noticed in the North Country. In one spot along the boardwalk, I found leaves from four different species of the red oak family, sometimes lying atop one another (see photo below), which I tentatively identified as red, black, pin, and scarlet oak. I say “tentatively,” because leaf shapes can be quite variable, and it is necessary to see acorns, leaf buds, and perhaps other factors to make an accurate identification.

October 31, 2025

Leaves from four species of red oaks that I found right next to each other on the boardwalk at Great Bay Nature Center. They all have pointed lobes, but they can be distinguished by the depth of the spaces between the lobes. Northern red oak (upper right) has the shallowest spaces, followed by black oak (upper left) and pin oak (bottom). The scarlet oak (upper middle) has spaces between the lobes that reach nearly to the center vein.

Back Home, With My Eyes Wide Open

Our visit to the Great Bay Nature Center jump-started a new interest in oak trees. Although we had lived full time in Sugar Hill for nearly twenty years, I had never noticed any leaves from white oaks or black oaks – only ones from northern red oaks. But now, with my eyes open and a curiosity buttressed by our walk by the Great Bay, I started to find leaves from other oaks no matter where I looked, including just outside our back door. Along Pearl Lake Road, along the trails at the Rocks, and in the middle of a field in Foss Woods, I found many leaves much more deeply lobed than northern red oaks. So, the northern red oaks are not alone. In addition to black oaks, there may be pin oaks and even scarlet oaks in our region

November 6, 2025 Black oak, pin oak, and/or scarlet oak leaves found at the Rocks Estate (left) and in

Foss Woods (right). These leaves all have deeper lobes than found on northern red oak leaves.

In Search of Scarlet Oak

Soon after finding the unexpected variety of oak leaves in Sugar Hill, we departed for our annual visit to our son and his family in Terre Haute. Along the way, I kept looking along the roadside for some of the scarlet oak trees that, according to my guidebook, really do turn scarlet in the fall. No luck driving through any small towns in New Hampshire, Vermont or New York. No luck at roadside rest areas in Pennsylvania or Ohio, although I did find some deeply lobed leaves that could have fallen from a scarlet oak and turned brown.

In Terre Haute, I continued my search in one of our favorite local parks, much to the chagrin of my family when I stopped again and again to take photos of oak leaves. Plenty of different oak leaves, but no scarlet oaks. The next day, we visited another local park, and there we hit the jackpot! A row of scarlet oaks fully justified their name by displaying their foliage against a snow-covered parkland. It was worth waiting for!

December 1, 2025

A row of scarlet oaks in Demining Park demonstrates the truthfulness of its name.

More and More Oaks

Indiana has no shortage of oak trees and no lack of diversity in oak species. After satisfying my desire to see scarlet oaks in full fall foliage, I continued to pick up many interesting oak leaves as I wandered through a half dozen other parks near Terre Haute. I mounted specimens on copy paper, took photos of them, and, eventually, sought to identify them using an immediately useful Christmas gift from my family: Marion Jackson’s field guide to the “101 Trees of Indiana”. To my surprise, this comprehensive list of Indiana trees included twenty species of oak – twenty percent of the total number of tree species found in the state! The range of leaf shapes is astounding, ranging from the bloated, top-heavy leaves of the black-jack oak to the skeletal lobes of the southern red oak.

Top Row: Black Jack Oak-Shakamak Park / Burr Oak-Hulman Forest / Chestnut Oak-Deming Park

Bottom Row: Chinkapin Oak-Turkey Run State Park / Northern Pin Oak-Dobbs Park / Southern Red Oak-Dobbs Park

The climate and geology of Indiana are very conducive to the growth of tall trees, and you have no problem finding huge oaks, tulip trees, and shagbark hickory trees towering more than a hundred feet over your head. At the end of the year, a multiplicity of oak leaves dominate the multi-inch carpet of leaves that we shuffle through while wall along trails in the parks.

Have you ever tried to estimate how many leaves are on the ground? Probably not. I love to count almost anything, but until shuffling along a leafy trail in Turkey Run State Park, I had never considered this not so vital question. The answer is simple: billions. Really. Billions of leaves created the thick blanket covering the ground in the oak forest that we were walking through. I did the math. The next photo shows over a hundred leaves in a couple of square feet. The forest covers a square mile or more, and a square mile has more than 25 million square feet. Multiplying that area by a hundred leaves per square foot produces an estimate of well over two billion leaves per square mile!

December 27, 2025

A three-inch layer of leaves covered the trails in Turkey Run State Park in Indiana.

Of course, we aren’t much interested in counting the trees in a forest, let alone worrying about the number of leaves on the ground. What we love is admiring a lovely leaf at the edge of a mossy stream or standing at the base of a huge tree gazing with awe straight up to the distant canopy, as shown below in a couple of photos taken in Turkey Run State Park.

One leaf at a time: a lovely leaf of a burr oak on a moss-covered rock at the side of a little rivulet.

One tree at a time: looking up to the canopy along the massive trunk of a giant oak tree..

And, when we have the chance to have a picnic on a sunny day in late October, we are happy for the view of the pond that opened up after the leaves dropped to the ground.

November 23, 2025 The leaves now cover the ground rather than the view from our picnic spot under the oak trees in Shakamak State Park near Terre Haute, Indiana.

Photos and text by Carl D. Martland, founding member of ACT, long-time resident of Sugar Hill, and author of Sugar Hill Days: What’s Happening in the Fields, Wetlands, and Forests of a Small New Hampshire Town on the Western Edge of the White Mountain. Quotations from his book and his journals indicate the dates of and the situations depicted in the photos.

Phenological Phacts and Photos with Carl Martland / December 2025

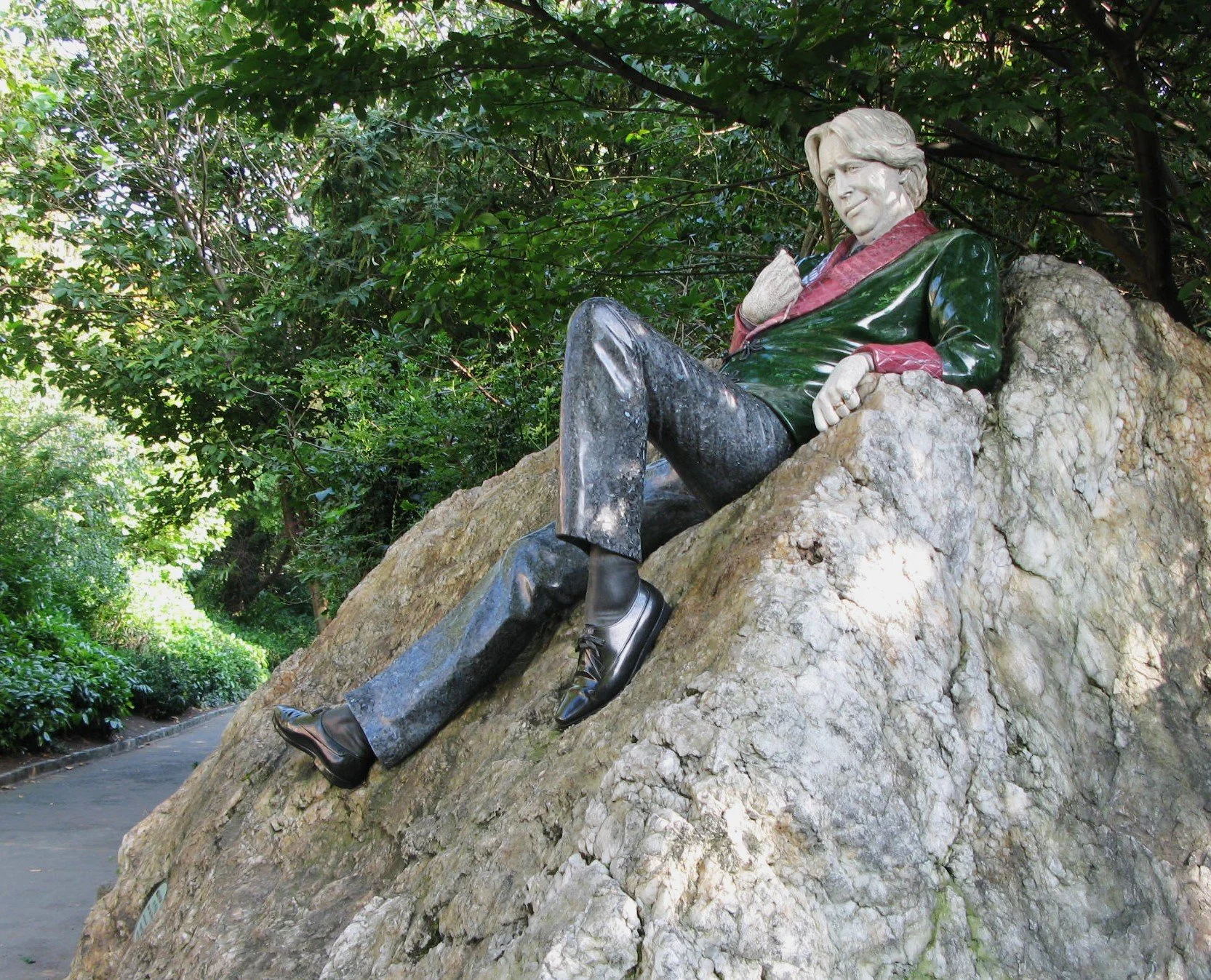

Oscar Wilde in Dublin

The Year in Review

Phenology – “a branch of science concerned with the relationship between climate and periodic biological phenomena (as the migration of birds or the flowering and fruiting of plants).”

Wilde Seasons

This end of the year is a good time for reflection, whether contemplating the great issues of the day or simply enjoying a mug of hot coffee in your favorite chair by the wood stove. In that spirit, instead of seeking some fascinating phacts about nature in December, I have reviewed this year’s phenological essays and selected my favorite photos and observations.

In January, I pondered a major discrepancy in our calendar. We still call many of our months by names that the ancient Romans chose to honor their gods, including Janus, Mars, and the first two Caesars. However, they apparently ran out of names, and we have been left with four months simply called Months 7 to 10. December, the end of our 12-month year, was only Month 10 according to the ancient Romans. Why? Because in Rome, March marked the beginning of spring and the time to plant their crops.

Those of us in the North Country cannot be convinced that March is anywhere close to the beginning of spring, but we do expect redwing blackbirds, woodcock and robins to show up while snow still covers most of the fields. And we can certainly agree with the phenological sentiments expressed so well by Oscar Wilde in “Ravenna”:

Now is the Spring of Love, yet soon will come

On meadow and tree the Summer’s lordly bloom;

And soon the grass with brighter flowers will blow,

And send up lilies for some boy to mow.

Then before long the Summer’s conqueror,

Rich Autumn-time, the season’s usurer,

Will lend his hoarded gold to all the trees,

And see it scattered by the spendthrift breeze;

And after that the Winter Cold and Drear.

So runs the perfect cycle of the year.

This poem was inspired by Wildes’s visit to Ravenna, the ancient capital of the empire after Rome was sacked. He, like many of us in the North Country, understood that the natural year logically begins in spring and ends in the cold darkness of winter. If you visit Dublin, you can spend some time bird-watching in Merrion Square Park, right across from where he once lived and where his statue continues to keep an eye out for the birds.

January - A Bird for Each Month Part I

The January and February essays identified one of my favorite birds for each month. Part I presented birds for January through June, and my overall favorite for this period was the cardinal. I recall seeing my first cardinal back around 1956 when we visited my cousins in Darien, Connecticut. Since cardinals had not yet made it to Rhode Island, I was very excited to see such a colorful bird. I also recall seeing my first cardinal in the North Country about 20 years ago, but my records and photos only confirm four more sightings before 2014. However, over the past ten years, cardinals have not only become regular summer residents, they now show up in the winter. Even the purple finch cannot top the brilliance of a male cardinal sitting in a snow-covered fir tree.

February 14, 2019

A cardinal sat in the fir tree, eyeing the sunflower seeds available in the feeder.

February - - A Bird for Each Month Part II

Part II nominated birds for July through December, and my overall favorite was the chestnut-sided warbler. Warblers typically arrive in Sugar Hill, in mid-May, and many of them will stay all summer. Some, like the black-throated green and the black-and-white warblers look for nests deep in the woods. Others, including the chestnut-sided, prefer the edges of the meadows. Getting a close-up view of this sociable bird is not a problem:

July 23, 1999, 90 degrees, humid, partly cloudy. I saw a chestnut-sided warbler in

an alder near the Upper Meadow. Actually, it saw me first and flew to a branch

about five feet away for a closer look.

If you see a warbler flitting about low alders or willows at the edge of a meadow in July, it may well be a chestnut-sided. If so, be patient, for once it notices you, it may well land a short distance away, and the male will be happy to show off its chestnut-colored flanks.

July 28, 2017

A chestnut-sided warbler paused long enough for me to catch his brilliant colors in this photo

March - Jabberwocky Explained

“’Twas brillig” is the start to Jabberwocky, a poem that Lewis Carroll published in 1872 and one that has enchanted generations of kids of all ages ever since. Carroll invented dozens of words for use in this poem, some of which have come into accepted usage, including chortled and galumphed, but most of them seem to most people to be as fantastical as the Jabberwock is supposed to be. However, I believe that this poem, at least the beginning, is an accurate description of what anyone might see around a pond in the beginning of spring, not only in Old England a hundred and fifty years ago, but right now in April in New England. Here are the first two stanzas:

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!”

The March PPP identified “slithy toves” as newts squirming around clumps of wood frog eggs (the “wabe”), while the “mimsy borogroves” (painted turtles) basked in the sun and “mome raths” (hooded mergansers) twisted their necks and poked their beaks into their feathers and cleaned themselves up. I then concluded that the Jabberwock must also be a real creature found near the same ponds where the other creatures are found. We also know that this poem tells us what a man said to his son who has taken his vorpal blade and is about to set off to find the Jabberwock. Now, a son could be a grown man, but it seems to me that this son is a boy with a vivid imagination who is heading off on an adventure with the approval of his father. Thus, the jabberwock could not be a bear; even though a bear certainly has jaws that bite and claws that snatch. No father would send his sun out to hunt a bear with a little blade, no matter how vorpal.

My belief is that the Jabberwock is a snapping turtle, which also has jaws and claws with the required abilities. Although a dangerous beast, a snapping turtle will stick its neck out a little too far for its own good, as shown in this photo of one that once crossed my path.

June 18, 2017

90 degrees, sunny. I went out to the solar array, planning to sit for a while in the shade simply enjoying the lupine. Imagine my surprise when a large snapping turtle stepped out onto the flat rock that is just about where I was planning to place my chair. Its shell was about 1 to 1 ½ feet long, its neck was thick, and its attitude toward me was somewhere between indifference and mild scorn. … It slowly advanced along the edge of the clearing and eventually found a suitable place to climb up the dam. For obvious reasons, I made no attempt to follow it!

As is evident in this photo, the long neck of a snapping turtle does provide an obvious target for someone armed with a vorpal blade. Furthermore, I know for a fact that boys have been known to hunt snapping turtles near ponds in New England, so presumably they have done so in Old England. My father grew up in Warwick, Rhode Island, and he told me that he used to capture snapping turtles in potato sacks and then sell them for fifty cents apiece to a neighbor who made turtle soup and marketed patent medicines with allegedly astounding – but unproven - benefits. My father had to use skill and great care to catch the turtles in a sack, because neither he, his brother, nor his father had a vorpal blade.

April - Nesting Season for Mergansers

Mergansers and Canada Geese arrive in Coffin Pond in late March or early April, even with fresh snow on the ground, so long as there is some open water. Common mergansers seek lakes and other large bodies of water, because they like to gather in small flocks. Hooded mergansers join them if they can’t find a small pond with ice out:

April 24, 2016

A pair of common mergansers at Coffin Pond.

March 25, 2020, 40 degrees, beautiful. We walked out the snow-covered trail next

to Coffin Pond, which was still two thirds iced over. A half dozen hooded mergansers

and a single common merganser were in the pond, while a pair of Canada Geese

floated across the river, eventually climbing out and huddling on the opposite shore,

their necks buried in their feathers.

June – Before the Lupin

In mid-April, the dam, like many of us, is depressed by the ever-lasting snow and ice. By mid-June, the dam, like many of us, is overwhelmed by the sheer variety and brilliance of the lupin. In between, in mid-May, when I walk along the dam, even though the new growth has barely begun, I know to look for the wild strawberries and violets that are usually the first flowers to break through last year’s detritus.

I look carefully for the tiny, easily missed flowers such as the blue-eyed grass, which has single flowers barely a half-inch across on stalks less than a foot tall, and I don’t ignore the beauty of the plentiful, but much maligned dandelion.

May 13, 2025 - Wild strawberries are the first blooms to be seen along the dam.

May 22, 2025 - A cluster of violets bloom adds a bit of color to the dam.

June 10, 2020 - A few of the tiny flowers atop the stems of blue-eyed grass can be seen in the latter half of May. By June, there may be dozens along the dam.

May 13, 2025 - If you think of dandelions as weeds, you probably haven’t noticed the delightful shades of yellow and orange of their blossoms.

July – Meadowhawks

From mid-July through mid-October, meadowhawks are among the most common dragonflies to be found around the pond. They are highly recognizable because of their size, the males’ red coloring, and their habit of resting frequently. Although only about an inch-and-a-half long, they are colorful, energetic, romantic, and photogenic. On any reasonably warm, dry, and sunny day in late-summer, you are likely to see a dozen or more bright red meadowhawks flying low over the water, resting on a twig, or clinging to the side of a cattail leaf in a heart-shaped wheel formed with their mate.

September 18, 2018

White-faced meadowhawks, the first meadowhawks to show up in July, are still active along the dam in mid-September.

White-faced meadowhawks usually arrive at the pond in mid-July, and they might be the only meadowhawks in the neighborhood for the next several weeks. These meadowhawks frequently linger on a twig or a flower stalk for a minute or more, providing plenty of time to zoom in and take pictures from several different angles highlight the variations in color from the dragonfly’s face to the tip of its abdomen.

August – Friendly, Frustrating Fritillaries

Fritillaries are large, colorful butterflies that are commonly seen throughout the North Country in late summer. At first glance, the fritillaries all look the same! In addition to good photos, you need an eye for detail, a guidebook, and perhaps a magnifying glass (for close examination of the photos in the guidebook). And you may also wish you had estimated the wingspan of the butterfly that you have photographed. The difficulty of species identification is why fritillaries are more than a little frustrating.

August 17, 2005

This photo of an Atlantis Fritillary captures the pattern of black spots on an orange background that defines fritillaries.

And there is one more reason for frustration. This butterfly and its favorite flower are two of the most difficult words that you could encounter in a spelling bee. Without looking back, can you say what comes after F-R-I-T …? Are you sure about the Ts and Ls? Are you sure whether that letter near the end is an A or an E? In my journal, I found multiple spellings, including frittilery, fritillery, and fritillary. To remember what’s correct, I now use the same method that a fellow consultant used to remember how to spell the tax on imports. Is it tarrif, tariff, or tarriff? Eric said it’s simple to remember: one R, two Fs With the fritillary, it’s one T, two Ls and an A. That’s not so hard, but how on earth are supposed to spell the flower whose name sounds like ACK – IN -NA – SHA?

September – It Begins After Labor Day

So much begins after Labor Day. The apples ripen, and the bears eat them up. Asters and goldenrods create brilliant colors along the roadside and in the fields, while bits of red and yellow appear in the maples and birches. The warblers, sparrows, geese and so many other birds begin their journey to warmer climes. Deer and turkeys worry, or should worry, about the beginning of the hunting season.

For me, a new life also begins after Labor Day, just it always has. As a student and throughout my professional career in university research, Labor Day marked the beginning of a new school year. Now, even though I have been retired for nearly twenty years, Labor Day still marks a new beginning. Summer for retirees is longer than, but not necessarily that much different from the vacations that we used to take. Only after Labor Day is it clear that we were not just having a lengthy vacation. The day after Labor Day, my calendar is still empty. I can do whatever I choose to do. Soon it will be time to pick the apples.

Make it stand out

September 14, 2022

The first batch of apples from the wild tree in the Lower Meadow. Should I begin with apple pie or applesauce?

October – Big Birds

I think that the Great Blue Heron is the most spectacular large bird in the North Country. In the fall, I always anticipate their arrival to hunt for young frogs. Sometimes, they stand still at the shoreline, patiently waiting for a frog to come to them. Other times they stalk along the shoreline, neck down and extended, ready to dart to either side if they see a frog. If I get too close, they will fly off, probably headed for better hunting at Pearl Lake or Coffin Pond, but a couple of times I’ve seen them land at the other end of the pond, and once I saw one land near the top of one of the tall pines on the other side of the road.

October 4, 2016

A Great Blue Heron stood by a group of Canada Geese at Coffin Pond

November – Fliers Fishing

Ospreys and eagles catch fish with their feet. Loons and cormorants use different tactics, operating more like the navy than the air force. In Wickford, RI, we once watched a bunch of cormorants feasting upon a school of fish that was heading from the bay, going under a bridge, and ending up in a little pond. I don’t know whether the fish were seeking something to eat in the pond or intending to swim further upstream to breed. The cormorants probably didn’t know either, nor did they care. What they did know is that there were so many fish, they could certainly catch a meal. We were amazed at the size of the fish compared to the size of the cormorant’s beak and throat.

September 15, 2016.

A cormorant struggles to figure out how to devour the fish that it has caught at the edge of Narragansett Bay in Wickford, RI.

December 2025 – Dreaming of Warmer Climes

And now it’s winter. The snow and ice have covered the landscape. So, back in your favorite chair by the wood stove, you can think about where you’ve been and pretend you’re back there, enjoying the sunshine. I’m thinking back to 2012, when we followed a little flock of white ibis strolling along a beach near Tampa Bay.

Final Exam

1. True or false: In the 1990s, Cardinals were commonly seen at bird feeders in the North Country.

2. A Jabberwock is:

a. A mythical beast

b. A mixed drink offered to tourists in pubs in England’s Lake District

c. A terrapin

d. None of the above

3. Spell the flower whose name sounds like ACK–IN-NA–SHA.

4. Essay (choose one topic)

a. Explain why you prefer to use your wild apples to make pies or apple sauce.

b. If you were a frog, would you be more scared by the arrival of a snapping turtle, a great blue heron, or

a phenologist pointing a camera at you?

Assignment for the Winter Break

Explain how a cormorant manages to eat a fish that is nearly a foot long.

(No more than five pages; use proper footnotes; identify all on-line sources.)

Participate in the Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count by documenting the Birds that you see between December 14 and January 5. For details click here.

Photos and text by Carl D. Martland, founding member of ACT, long-time resident of Sugar Hill, and author of Sugar Hill Days: What’s Happening in the Fields, Wetlands, and Forests of a Small New Hampshire Town on the Western Edge of the White Mountain. Quotations from his book and his journals indicate the dates of and the situations depicted in the photos.

Phenological Phacts and Photos with Carl Martland / November 2025

Fish Stories

Phenology – “a branch of science concerned with the relationship between climate and periodic biological phenomena (as the migration of birds or the flowering and fruiting of plants).”

Joys of Fishing

Several of my neighbors are avid fisherman. Doug and Dan have been fishing since they were kids, and they have the gear – vests, flies, multiple rods, and huge hip boots that allow them to seek the best spots in the Ammonoosuc. When we first moved in, Harry would offer to tell us some good (but probably not his best) spots to fish, and he knew well how to tell a fish story. Becky, growing up in an urban world, had yet to learn the art of fly fishing, but she was soon seen out by the pond practicing her new fly rod. Dan was an avid member of Trout Unlimited, and he had trouble looking out at the pond every morning, knowing that it had no fish. Eventually, they convinced us to let Fish & Game drop some trout in the pond, and soon the fish were jumping.

September 11, 2003 70 degrees. The fish were jumping in both ends of the pond, much more than they had been during the summer.

May 15, 2004, 80 degrees at 9am. The trout lilies are gone by; meadowsweet, apple and cherry trees, dandelion, and wild strawberry are blooming. Fish are jumping, green darners patrolling, bullfrogs rumbling, and turtles sunning.

I bought a cheap fishing rod, and Nancy and I did catch some fish. Our best year was way back in 2006. My journal entry summing up that year’s catch came after the best day either of us had ever had fishing:

September 30, 2006. I caught four fish in July; Tony caught five during his visit; and Nancy and I caught a remarkable 9 fish in a half hour on September 16th, for a total of l9 for the year.

Poachers

Of course, when a new fishing hole is found, word gets around the neighborhood. And, as is the case with apples and vegetable gardens, we find that we are not alone in our desires.

August 10, 2006. An osprey flew down and carried off a trout from the pond.

Nancy still talks about our remarkable success that September day back in 2006, but I can just as well recall the osprey speeding in low over our end of the pond, claws extended, hitting the water, and flying off holding a trout lengthwise below its body. Unfortunately, I haven’t seen another osprey fishing in our pond since then.

But other critters have been around:

May 27, 2005. Dan Kennerson said he saw a mink in the pond after the ice melted. He said there was a lot of fish kill over the winter.

A mink is a small weasel, and though I’d also seen one in the pond, I thought it would be a greater threat to the frogs than to the trout. Otters, however, are much larger, and they certainly were attracted by the trout stocked in our pond. They are big enough that they could, if they wanted to, eat a lot of fish. And, that is one thing they do want to do. In 2016, a pair of otter were in our pond for more than two weeks, and I suspect they made a serious dent in the fish population.

September 27, 2016, 11am. A pair of otters were in the pond, diving, tumbling, and swimming underwater. At one point, they each barked, but didn’t leave the pond. I didn’t see that they caught any fish … When I went back to the pond at 3pm, the otters were still there.

Ok, I caught them in photos that first day, but not in the act of actually eating fish. So I couldn’t charge them with anything but taking a swim, which is not a crime. However, soon further evidence appeared:

September 29, 2016. Fresh scat filled with fish scales by the southeast corner; presumably the otters that I had not previously found guilty of poaching.

And they returned again and again to the scene of the crime:

September 30, 2016, noon. A pair of otters circled the pond, up and down, one to ten feet off shore or out from the reeds. They would swim three to 15 yards under water, pop up for a breath of air, then go right back down. One even got out on Rock Island (damn – I forgot my camera!). Then they went around again, once in a while spending a few seconds on the surface, maybe sniffing.

And I guess seeing otters became rather commonplace that fall, as my final entry was brief:

October 14, 2016. Otter in the pond.

Native Fish in Sugar Hill

Dan, Becky, and Doug, possibly because of unfair competition from the otters, prefer to spend their time bashing through the underbrush to get to their secret spots along various near-by rivers. To me it seems like a lot of work, but I certainly share their love of being in the wild, listening to the rushing water, enjoying the sunshine and being away from all responsibilities. I get much the same feeling, with much less effort and no preparation at all, by sitting in my Adirondack chair at the Point.

July 14, 2018. Doug and I went down to the Ammonoosuc River where the iron rail bridge brings the Rail Trail across. Doug waded through the river with his fly rod, while I checked along the edge of the river for insects

On the other hand, I do have to acknowledge that I will occasionally plow through the goldenrod, cattails, and young willows to get to a stream, not trying to find a nice fishing spot, but hoping to get a nice photo of dragonflies, frogs, or turtles. A couple of times I’ve come out of the brush in the Lower 40 or Creamery Pond to find small schools of dace or native trout in Salmon Hole Brook. Dace, a species of minnow easily identified by the black strip along their sides, live in cool, sluggish streams that afford cover under trees or logs. The largest one in the photo below is about four inches long.

June 17, 2019, 75 degrees, beautiful. In the afternoon, I went down to the Lower 40. More big trees have fallen across and by the wall trail, making it a little harder to get to the brook, where I took photos and videos of a couple dozen dace congregating near the shore.

The trout that live in the upper end of Salmon Hole Brook are about the same size, which makes them of much more interest to the naturalist than to the fisherman. In brooks that are a little deeper and wider, larger trout can be found. After all, the Salmon Hole Brook is named for Salmon Hole, a famous fishing spot right before the brook meets the Ammonoosuc River.

August 14, 2017. After taking a walk through the Sugar Hill Town Forest, I stopped to take a look down the power line right-of-way, which crosses Crane Hill Road at the bottom of a little valley. When I glanced down at the little brook that flows under the road, I was happily surprised to see a couple of good-sized trout not ten feet from the pavement. So I caught them – on film.

Flyers Fishing

Spend enough time by the shore of a large body of water, and you most likely will see some fish caught without the help of a fly rod or a hook. I’m thinking of flyers fishing, which you should not confuse with either fly fishing or flying fish.

A highlight of every visit to the wildlife sanctuary on Great Bay near Portsmouth has been the sight of ospreys or their huge nests. Once we saw an adult standing on its nest, looking down at a youngster that was just able to lift itself high enough to see over the edge of the nest to the wide world. Even better was the time that an osprey landed on the bare branch of a distant tree. We could see that it was holding something, that with binoculars, we confirmed was a good-sized flat fish. It was far away, so the best I could do was to get a few fuzzy photos and videos of the osprey enjoying its meal.

May 28, 2023, Great Bay. An osprey landed on a distant branch with a flatfish in its talons. It eventually settled down and proceeded with lunch.

Ospreys and eagles catch fish with their feet. Loons and cormorants use different tactics, operating more like the navy than the air force. In Wickford, RI, we once watched a bunch of cormorants feasting upon a school of fish that was heading from the bay, going under a bridge, and ending up in a little pond. I don’t know whether the fish were seeking something to eat in the pond or intending to swim further upstream to breed. The cormorants probably didn’t know either, nor did they care. What they did know is that there were so many fish, they could certainly catch a meal. We were amazed at the size of the fish compared to the size of the cormorant’s beak and throat.

September 15, 2016. A cormorant struggles to figure out how to devour the fish that it has caught at the edge of Narragansett bay in Wickford, RI

Loons have the same problem. They can catch the fish, but then they have to figure out how to eat it. The picture below is a from a video taken at Fort Foster, across the channel from Portsmouth Naval Base. The loon had dived repeatedly before coming up with this fish, which it promptly dropped. The loon kept at it, quickly caught the stunned fish, and worded at securing the fish in a position suitable for taking a bite. Eventually the loon was satisfied, and it proudly swam away looking for a spot to enjoy its meal.

April 27, 2023. A loon grappled with a fish it had caught just off the rocky shore by Fort Foster, Kittery Point, Maine

Fish Stories

As near as I can tell, much of the joy of fishing comes from telling the tales. “The one that got away.” “I caught twenty fish – all catch and release, forgot my camera.” “Here’s a picture of the giant tuna that I caught all by myself.”

Even though I have seldom had any success fishing, I do know how to tell a tale. And here is a tale that I wrote down back in 2009 in preparation for a visit from our son and his family along with his sister-in-law and their three kids. The idea was to collect stories and accounts of activities in notebooks entitled “Sugar Hill Days” that Nancy had prepared for each of us. As with many well-laid plans, the only entry in my book was the following tale, written with a red sharpie, which I think qualifies as a proper New England fish story.

My Fish Story

by Carl

June 2009

One misty evening, after wasting most of the afternoon fishing, catching only three trout, none larger than 20 inches or 3 pounds, I decided not to fret about catching anything large enough to keep and began to practice my casting. Standing on the rock at the Point, I practiced bouncing the lure off the drain, hitting the tin the usual 3 times in 4 casts. But, success being boring, my mind wandered and on the next cast the line went right down the drain pipe. I tried to reel it is, but the line seemed to be stuck, so I let out line and walked around to the other side of the pond so I could see what the problem was.

It took a while, because a week of rain had left most of the trail a swamp. I finally got to the other side, leaned over the drain and looked down inside. I couldn’t see a thing. The line, though, was very tight and I couldn’t pull it in at all. After struggling a few minutes, the line gave way, I reeled in 3 feet, when it got stuck again. And then I heard a horrible thrashing on the other side of the dam, by the exit of the drain pipe.

I went over and was amazed to see the head of the largest trout I had ever seen – and it was thrashing trying to escape for the pipe. I could see my line emerging from the corner of its enormous mouth. There was no way I could get it out alone, so I called John Peckett. He came by and hitched up a winch to his truck and we tied a half-inch line around the middle of the fish. A half hour later, we had the fish out of the pipe, into a vat usually used for maple sap, ready to be taken to the Sugar Hill Museum for display. While all this was going on, we picked up two 22-inch trout from the pipe, which we had for supper.

Photos and text by Carl D. Martland, founding member of ACT, long-time resident of Sugar Hill, and author of Sugar Hill Days: What’s Happening in the Fields, Wetlands, and Forests of a Small New Hampshire Town on the Western Edge of the White Mountain. Quotations from his book and his journals indicate the dates of and the situations depicted in the photos.

Phenological Phacts and Photos with Carl Martland / October 2025

Anticipated Avian Arrivals

Phenology – “a branch of science concerned with the relationship between climate and periodic biological phenomena (as the migration of birds or the flowering and fruiting of plants).”

Small Birds

If you’re a dedicated bird watcher, you have been anticipating the fall migration, hoping to see the many species of warblers, sparrows and other songbirds as they make their way south.

October 9, 2020, 34 degrees, 9:30-10:30am. At 2:00 in the afternoon, a half dozen bluebirds enjoyed the bird bath and inspected the front yard bird house. A while later, a yellow-rumped warbler, a pine siskin, and a half dozen robins simultaneously foraged across the front yard.

Yellow-rumped warblers are the most common warblers passing through Sugar Hill, and I am happy to watch them as they bounce from perch to perch on the patio or at the edge of the pond. The other migrating warblers are harder to see and much more difficult to identify without a good photo and a guidebook. But I am happy for just a quick glimpse of one of these little birds, because they may soon return and pose a little bit closer, even at the end of October.

October 20-21, 2013. Several oven birds were in alder clumps and small trees near Joe Pye Hill, and yellow-rumped warblers were in the lilacs and birches in the front yard. A small flock of juncos, a blue jay, and a pair of bluebirds were in the yard on the 21st.

A few years ago, I was especially thrilled to get a photograph of a Tennessee Warbler, a lovely creature that I’d never seen before in our yard.

October 12, 2020, 53 degrees, sunny, breezy. A Tennessee warbler was in the fernery – a lifer documented in a photo.

OK. I know what you’re thinking. “Seeing this nondescript little yellow bird is supposed to be thrilling? Birdwatchers are weird!” So, no more about hard to see and harder to identify little birds. Let’s talk about the big birds whose arrival everyone anticipates.

Turkey Time

By October, flocks of young turkeys are wandering the countryside with their mothers, and lonely males, known as Jakes, are apt to be strolling through the fields and along the roadsides with a couple of their buddies. I bet that anyone over two years old can identify a turkey, and everyone, even the weirdest birdwatcher on the lookout for a Nashville Warbler, is excited to come across a flock of turkeys at the side of a country road.

October 24, 2019. I came across a dozen turkeys grazing along the side of Valley Vista Road in Sugar Hill.

Looking for Lunch

Early fall is also a good time to watch out for hawks. Up and down the East Coast, bird watchers know where to go to witness countless numbers of hawks streaming down toward their winter quarters. Oops! Did I say countless? That’s only for the uninitiated, which unfortunately are likely to include nearly everyone who is reading this. Of the many spots where those in the know gather to count the hawks, the best location is Cape May Point State Park in New Jersey, where birdwatchers gather each fall to count the numbers of hawks flying down the coast. I repeat – to count each and every hawk that flies within sight of the viewing platform. Here is a sample of the type of information that they gather:

In 2022, 47,029 individuals were counted, with the most common species being the Sharp-shinned Hawk, checking in at 15,018 individuals. Early in the season is the best time to see falcons, such as Peregrines, Merlins, and American Kestrels. Later, chances are better for the larger species, such as Bald and Golden eagles. Fall Bird Migration is in Full Swing in Cape May.

Around here, there are too few hawks for any such count, and I seldom see even one hawk flying overhead. So I don’t watch out for hawks. But others do! Redwings, swallows, catbirds, and all the summer residents have to teach their young not to dilly dally out in the open. If they see a hawk’s shadow speeding across the lawn or the pond, they yell (chirp??) “Watch Out!!” Their kids need to be lucky if they are not careful, for I might not be the only nearby birdwatcher.

August 24, 2017, 10:30am, 70 degrees. A Cooper’s hawk landed in the dead apple tree on the other side of Post Road, then took off and flew over the lilacs toward the back yard. Soon a catbird popped up crying. Did the hawk catch lunch?

We only get a good view of a hawk when it is hunting, whether hoping to catch a bird or a chipmunk.

September 20, 2013. A Cooper’s hawk was sitting still on the front lawn for several minutes, looking like an eagle sitting on a beach on Vancouver Island. It flew off before I managed a photo, so I went out hoping to figure out what it was doing. I don’t believe it was a coincidence that it was posted right next to a hole that was about two inches in diameter. My recent sightings of Cooper’s Hawks flying low over the lawn may also have been cases where I had interrupted their vigil, as they sat patiently waiting for a careless chipmunk or mole to emerge from its den.

Even if the youngsters are not careful, the neighborhood watch-dogs (watch-birds?) may keep both the young birds and the unwary rodents safe;

September 20, 2015. A couple of crows uttered low, ugly, guttural exclamations. I looked up to see a medium-sized hawk flying close to the tree-tops, from one tree to another, where another crow said, once again in guttural crowish, “Hit the road, Jack.” The hawk understood, circled a couple of times, and headed off.

Hawks and owls pretty much ignore the birdwatchers, and they are willing to sit still on a porch or a fence waiting for an unwary squirrel or mouse to show up on a mowed lawn or a songbird to come to the feeder. That is when I’ve taken my best photos.

December 16, 2018. I took nine photos of a red-shouldered hawk sitting on a fence next to a ball field in Terre Haute.

March 9, 2011. Jeanie called to say a hawk was perched on her bird feeder. Five minutes later, it was still there.

Hawks aren’t the only predator to menace our resident creatures. The most dangerous, of course is the automobile, deadly not only to the small and unwary, but also to the large and over-confident. Over the past 75 years, the construction of the Interstate Highway System has provided a steady supply of road kill, and that has allowed turkey vultures to expand their range to the North Country. Turkey vultures are not high on the beauty scale, but they do serve a useful function by helping to clean up what our cars have destroyed. At least that is what I’ve been told. Myself, I’ve only seen them circling high overhead.

September 17, 2016. I managed to get a photo of a turkey vulture that was gliding over the field on the other side of Pearl Lake Road. It has huge wings, which it holds at angle, and it wobbles as it circles looking for lunch.

Hawks and turkey vultures are the most commonly seen predators circling over our yard, but they aren’t the only ones. Ospreys, harriers, and even a rare eagle have flown over the pond looking for a meal.

October 22, 2021, 1030am, 60 degrees, cloudy. A very large hawk – possibly an eagle – flew in low over our lawn and out toward the Upper Meadow. I ran out with my camera in time to see it fly back right over my head, so close that I could hear its wings beating. The only characteristic that made a clear impression was that its beak seemed long, curved, and dangerous. Its head may have been lighter than its body, but I didn’t think it was bright white. Its wings were rounded rather than pointed, and its overall shape was that of a bald eagle.

I never got a photo of this bird, but Sibley’s Field Guide has pictures of eagles as seen from below. From this angle, which is the exact view that I had enjoyed, the bill is prominent and you can’t see the white head. So yes, I am pretty certain that this was one of my rare sightings of bald eagles in Sugar Hill.

Hunting Frogs

I think that the Great Blue Heron is the most spectacular large bird in the North Country. In the fall, I always anticipate their arrival to hunt for young frogs. Sometimes, they stand still at the shore line, patiently waiting for a frog to come to them. Other times they stalk along the shore line, neck down and extended, ready to dart to either side if they see a frog. If I get too close, they will fly off, probably headed for better hunting at Pearl Lake or Coffin Pond, but a couple of times I’ve seen them land at the other end of the pond, and once I saw one land near the top of one of the tall pines on the other side of the road.

October 22, 2021. At 2pm, a Great Blue Heron was standing by Kennerson’s dock. I managed a picture just as it flew up, and then it circled around and landed just past the big larch on the trampled cattails, allowing me to get some more photos. At 5pm, the heron was standing on Rock Island.

In October, Great Blue Heron can also be seen at large ponds or lakes, perhaps with a couple of families of Canada Geese as they all get ready for their long flight south.

October 4, 2026. A Great Blue Heron stood by a group of Canada Geese at Coffin Pond.

You might see an eagle high overhead if you stop at Coffin Pond to see if there are any geese or heron, but if you really want to see eagles, you should go to one of the beaches along the eastern coast of Vancouver Island. Out there, eagles are about as common as sea gulls on Cape Cod. When you walk out onto the rocky beach, an eagle might even turn its head, look closely at you, and seemingly invite you to sit down and enjoy the view.

April 2, 2017. One of the many eagles that we saw sitting on beaches and sand bars near Comox on Vancouver Island in British Columbia.

Photos and text by Carl D. Martland, founding member of ACT, long-time resident of Sugar Hill, and author of Sugar Hill Days: What’s Happening in the Fields, Wetlands, and Forests of a Small New Hampshire Town on the Western Edge of the White Mountain. Quotations from his book and his journals indicate the dates of and the situations depicted in the photos.

Phenological Phacts and Photos with Carl Martland / August 2025

Friendly Frustrating Fritillaries

Phenology – “a branch of science concerned with the relationship between climate and periodic biological phenomena (as the migration of birds or the flowering and fruiting of plants).”

Friendly, Frustrating Butterflies

Fritillaries are large, colorful butterflies that are commonly seen throughout the North Country in late summer. The picture above captures the pattern of black spots on an orange background that defines the fritillaries.

Fritillaries encompass two genera: Silvered Fritillaries (Speyeria) and Lesser Fritillaries (Boloria). I went on-line to find the meaning of these Latin words, and an amazing web-site translated Speyreria and Boloria into Speyeria and Boloria and further informed me that they were groups of butterflies. Another search resulted in the same thing, but further informed me that Speyeria butterflies are sometimes called the “Greater Fritillaries” as well as Silvered Fritillaries. OK. These AI programs never studied Latin. At least they tell us that there are two groups of fritillaries, big ones and little ones.

In the North Country, we can expect to find three species of the big ones (Great Spangled, Aphrodite, and Atlantis.) and three of the little ones (Silver-bordere, Bog, and Meadow Fritillaries.)

Fritillaries abound when Joe Pye Weed, echinacea, and lilies bloom in late summer. These are friendly butterflies, quite happy to pose on these flowers or any available perch found on the roadside or along the shore of a pond. I have hundreds of close-up photos of these large, intricately-patterned, distinctive creatures, which suggests that I should easily be able to select lovely photos of the half dozen species found in the North Country. Don’t I wish that were the case!

At first glance, the fritillaries all look the same! In addition to good photos, you need an eye for detail, a guidebook, and perhaps a magnifying glass (for close examination of the photos in the guidebook). And you may also wish you had estimated the wingspan of the butterfly that you have photographed. The difficulty of species identification is why writing this essay has been more than a little frustrating.

It was especially aggravating to find the following quote in Paul A. Opler and Vichai Malikul’s Field Guide to Eastern Butterflies:

“In some western areas, several species occurring together may be difficult to identify, but our eastern species usually pose no problems.”

My experience suggests that identifying species always poses problems – unless you don’t care whether your identifications are correct!

First Encounters

Since I have all of my journal entries in a single file, I can quickly find all mentions of fritillaries just by searching for “fritillary.” I have also sorted my photos of fritillaries in a a series of folders on my computer - one for Sugar Hill, one for New Hampshire, and several for other locations. When I started working on this essay, I searched for interesting entries about fritillaries and then looked for photos that could be used in this essay. In many cases, I could find a journal entry that described something about a photo I had selected.

As I pursued this type of inquiry for too many hours, I recalled that my friend Tony was responsible for my initial interest and knowledge of fritillaries. Tony is a Master Naturalist, and we have made many excursions in search of wildlife in the forests, sea shores, and wetlands of New England and Virginia. He and his wife Shirley retired to the Eastern Shore of Virgina nearly thirty years ago. On one of our first visits to his new home, he led us through the fields and forest to an opening created by a recent clear-cut. Nancy and I were listening to bird song and marveling at the abundance of wildflowers and tiny trees when suddenly Tony shouted out “OMG, a fritillary!” Nancy and I, glanced at each other, highly amused by Tony’s excitement, and I politely asked the obvious question: “What is a fritillary?” Tony groaned at our ignorance, then explained that it was a beautiful butterfly rarely seen in that part of Virginia. I didn’t actually see that fritillary, but I’ll never forget Tony’s excitement.

A couple of years after that, Tony again brought fritillaries to my attention as we went for a walk around the Pond.

August 17, 2003. Four turtles sunning at the point caught my interest, but Tony was more excited by the butterflies on Joe Pye Hill: a viceroy, fritillaries, wood nymphs and wood satyrs, and skippers.

I finally managed to take some photos of fritillaries in July 2005. The one below shows one sitting on an echinacea, a tall flower with a magnificent blossom. I now know that fritillaries love echinaceas. When these flowers are blooming, I make sure to bring my camera out to what is likely to be an outstanding photo op.

July 26, 2005. A good day for butterflies. I took a picture of a large fritillary on Nancy’s mound garden.

A couple of weeks later, Tony and Shirley visited, and we spent a bright, sunny afternoon at Pondicherry. I was making a list of the butterflies and dragonflies that we encountered as we walked down the rail trail when Tony, nearly as excited as he had been in Virginia, pointed out what he identified as a Silver-bordered Fritillary sitting on a leaf at the side of the trail. This identification could only have come from Tony, the inveterate Master Naturalist who hosted butterfly observation days on his own fields in Virginia.

Thinking that this early sighting of a fritillary would fit well into this essay, I looked for and eventually found the picture I took on that day. Imagine my surprise when I found that the photo was mistakenly labeled “Atlantis Fritillary”. Tony recognized this butterfly as a Lesser Fritillary, one that looks like but is much smaller than the Atlantis Fritillary. I realized my mistake only when working on this essay, and that is one cause of my frustration with these butterflies!

August 19, 2005. Tony and I went it to Pondicherry. A great day for butterflies: Northern Pearly Eye, Crescents, Viceroys, Harris Checkerspot, and Silver-bordered Fritillaries. The fritillary only goes about 3-10 feet per hop along the shore or along the road.

And there is one more reason for frustration. This butterfly and its favorite flower are two of the most difficult words that you could encounter in a spelling bee. Without looking back, can you say what comes after F-R-I-T …? Are you sure about the Ts and Ls? Are you sure whether that letter near the end is an A or an E? In my journal, I found multiple spellings, including frittilery, fritillery, and fritillary. To remember what’s correct, I now use the same method that a fellow consultant used to remember how to spell the tax on imports. Is it tarrif, tariff, or tarriff? Eric said it’s simple to remember: one R, two Fs. With the fritillary, it’s one T, two Ls and an A. That’s not so hard, but how on earth are supposed to spell the flower whose name sounds like ACK – IN -NA – SHA? I used this word above and it passed the spell checker, so you take a guess right now and then check to see if you’re correct. There are so many possible spellings that I can’t begin to think how Eric would have handled this.

The Greater Fritillaries

If a fritillary has a wingspan nearly as wide as the back of your hand, then it is one of the Greater Fritillaries. If its forewing has a black border, then it is an Atlantis Fritillary. In the photo below, the black borders of this large fritillary’s indicate that it is an Atlantis Fritillary.

July 18, 2020, 75 degrees, sunny, breezy, great! In the afternoon, I went to the power lines to photograph butterflies. Fritillaries, skippers and commas active along Pearl Lake Road.

The other two Greater Fritillaries found in the North Country lack the black border. The Great Spangled is larger, which doesn’t help if you’re just looking at one fritillary or at a photo. A better characteristic is the width of the yellow sub-marginal band on the underside of the hind wing, which is wide for the Great Spangled and narrow for the Aphrodite.

Aphrodite Fritillary, July 26, 2005. Notice the narrow band of yellow toward the outside of the hind wing.

Great Spangled Fritillary, July 13, 2019. 2005. Notice the wide band of yellow toward the outside of the hind wing.

The best characteristic is when there is a great size difference between two large fritillaries. This can be easy to see if a bunch of fritillaries are buzzing around a patch of Joe Pye Weed, but you have to be sure to note which ones are the large ones. The photo below is a rare one that captures two fritillaries; the butterfly in the back has a 13% greater wingspan even though it is further from the camera, so that is indeed a Great Spangled Fritillary. A different photo of the smaller one showed the black border on its wings, confirming that it was an Atlantis Fritillary.

July 26, 2005. One of my first photos of fritillary turned out to be the only one of mine that shows two species visiting the same flowers.

The Lesser Fritillaries

According to Warren J. Kiel’s guidebook The Butterflies of the White Mountains of New Hampshire, the Silver-bordered and Meadow Fritillaries are found in open fields and moist meadows, while the Bog Fritillary’s habitat is limited to good-sized sphagnum-moss bogs. If you’re not sinking into a bog, then the very small fritillary you’ve found will either be a Silver-bordered or a Meadow Fritillary. A close inspection will show whether or not there is a black border along the edge of its forewing. If so, then it is a Silver-bordered Fritillary; if not, then it is a Meadow Fritillary. The meadow fritillary is also the only fritillary lacking the conspicuous white spots on the underside of its hind wing.

August 18, 2020, 70 degrees, partly cloudy, 1530-1600. A small fritillary in the front yard, which I later identified to be a Meadow Fritillary, is the only fritillary that lacks the usual silver spots found on the underside of their hindwings.

I have already mentioned that my friend Tony identified some Silver-bordered Fritillaries that we came across walking along the rail trail in Pondicherry twenty years ago. When I searched through my journal entries and my photographs of fritillaries, I found no further evidence of one of these. However, I was pretty excited when I came across this entry::

August 23, 2021, 84 degrees, mostly cloudy. Photos of fritillaries:

· 1628: medium-sized, by the end of the dam.

· 1636: very large, probably a Great Spangled, on asters on the dam.

· 1640: very small, on asters on dam

I eventually found these three photos, all of which I had identified each as an Atlantis Fritillary, because they each had the requisite black border on their forewings. However, since my journal entry cited the great difference in size, I took a closer look at the photos. The very large one and the medium one were indeed Atlantis Fritillaries, but the one that I had observed to be “very small one” wouldn’t be any of the Greater Fritillaries, and the Silver-bordered Fritillary is the only Lesser Fritillary in our region that has a black border on its forewings.

August 23, 2021. This Silver-Bordered Fritillary looks pretty much like an Atlantis Fritillary, because of the black border on its wings. However, when I found that I had noted that it was “very small,” I realized that it was one of the lesser fritillaries, and the other two options lacked the black border.

When and Where to Look for Fritillaries

I only have a few journal entries of any of the fritillaries in June or after Labor Day. The best time to see them will be on a sunny day in late summer.

July 31, 2016, 70 degrees and cloudy at 11am; the first chilly morning in a long while. By mid-afternoon, it was very quiet by the pond. Only a couple of redwings calling in the reeds by the pond. When the sun came out, a few bullfrogs made a dispirited attempt to start a chorus; one would call, but it would be 15-30 seconds before another one would answer. I was bored with the lack of activity in the pond, so I went to Joe Pye Hill, where the bees buzzed and a great spangled fritillary posed with its wings open for several pictures.

The ideal conditions for fritillaries and other late summer butterflies came on a cool, calm day in early September back in 2019:

September 3, 2019, 64 degrees, partly sunny. At 4pm, it was now mostly sunny and absolutely calm, so that the pond was a mirror, great conditions for what was the best butterflies of the year, and perhaps of our 22 years:

At least four monarchs on asters at the far end of the dam, two or three at our end, and four or more on Joe Pye Hill.

A viceroy, a sulfur, a red-spotted purple and common ringlets joined the monarchs along the dam.

A great-spangled fritillary chased another one of the monarchs at the end of the dam.

Where to look for fritillaries? Gardens, meadows, overgrown meadows, roadsides. Keep your eyes open and your camera at the ready. But get out before Labor Day, or your summer, like this last fritillary, will be a blurred memory.

Photos and text by Carl D. Martland, founding member of ACT, long-time resident of Sugar Hill, and author of Sugar Hill Days: What’s Happening in the Fields, Wetlands, and Forests of a Small New Hampshire Town on the Western Edge of the White Mountain. Quotations from his book and his journals indicate the dates of and the situations depicted in the photos.

Phenological Phacts and Photos with Carl Martland / July 2025

Darners, Pogo Sticks and Red Skimmers

Phenology – “a branch of science concerned with the relationship between climate and periodic biological phenomena (as the migration of birds or the flowering and fruiting of plants).”

First Encounters

My first encounters with dragonflies and damselflies happened back in the mid-1950s when I went down with my pals to Warwick Pond for a swim on hot summer days. I was a little scared of the long, thin insects that flew around us while we splashed in the water. Since we were told that these were “darning needles” and “sewing needles,” we had reason to believe that they could deliver a pretty sharp bite. This unwarranted belief may have subconsciously dampened any interest I might have had in what I now know to be harmless, beautiful, and altogether delightful creatures.

As I grew up, I became interested in birds, butterflies, trees, wildflowers, mammals, hiking, camping and just about anything else connected with the natural world. Except dragonflies and damselflies. I made it all the way to my 50th birthday having learned only the most basic things about these insects. I knew that the so-called “sewing needles” were totally benign bluets, a damselfly commonly seen swarming low over any New England pond on warm summer days. I also knew that the “darning needles” were actually darners, a prominent class of dragonflies that includes the ever present green darner. And that was about it.

Then, in 1997, we purchased an old farmhouse in Sugar Hill that came fully equipped with a one-acre pond surrounded by woods and meadows. I swam in the pond, I cut trails around the pond, I watched birds and bats fly over the pond, and I enjoyed reading books sitting in an old Adirondack chair that I had positioned at the edge of the pond. I couldn’t help but notice the many dragonflies and damselflies flying around the pond, and eventually, at the end of our second summer in Sugar Hill, I finally mentioned dragonflies in my diary:

August 7-9, 1998. Several pairs of skimmers were laying eggs on the surface of the pond. They appear to bounce off the surface after touching the surface of the water with her tail, much as if he were using her as a pogo stick.

These dragonflies clearly weren’t green darners, which was the only dragonfly that I was then able to identify, and I had no guidebook to help me out. So, I did what had to be done - I invented names for them based upon their behavior:

July 22, 1999, 86 degrees, somewhat humid. The dragonflies defend their territory aggressively, especially against others of the same species. Red skimmers appeared yesterday for the first time this year, and a lone female was laying eggs in water about 2-feet deep, near the rocks, and five to ten feet off the shore. The other species would chase her off, but she’d slip back in.

August 29, 1999. “Pogo Stick” dragonflies laying eggs near dock. I counted one pair making over 30 bounces.

After these early entries, my journals make no mention of red skimmers or pogo stick dragonflies until the late summer of 2003:

August 8, 2003, 4pm, by pond. Two red skimmers were at the point, and a green darner was laying eggs off low cattails by the dock.

September 14, 2003. Red skimmers were laying eggs in the pond, from 10 feet off shore to the middle by the point and by the log. I saw one pair make 165 bounces! She laid an egg every 6 – 18 inches, bouncing 6-12 inches up after each egg was dropped.

My seventh summer in Sugar Hill and I was still referring to red skimmers and pogo stick dragonflies! Embarrassing! But, soon thereafter, I finally obtained a guidebook - Sydney Dunkle’s “Dragonflies Through Binoculars: A Field Guide to the Dragonflies of North America” - and I quickly learned that the red skimmers and pogo stick dragonflies are meadowhawks. The next summer, armed with a new digital camera, I began to take photos of these delightful dragonflies.

September 6, 2004. My first photo of meadow-hawks shows one pair laying eggs near the Point, while another male passes by. The tiny white dots are probably eggs that she or other pairs had recently laid on the surface of the pond.

The Allure of Meadowhawks

From mid-July through mid-October, meadowhawks are among the most common dragonflies to be found around the pond. They are highly recognizable because of their size, the males’ red coloring, and their habit of resting frequently. Although only about an inch-and-a-half long, they are colorful, energetic, romantic, and photogenic. On any reasonably warm, dry, and sunny day in late-summer, you are likely to see a dozen or more bright red meadowhawks flying low over the water, resting on a twig, or clinging to the side of a cattail leaf in a heart-shaped wheel formed with their mate.

Five species of meadowhawks can be seen around small ponds in our region:

White-faced meadowhawks