How do those insanely loud spring peepers go from ice cubes to sex machines in a matter of days?

Creature Feature: Journey of the Monarchs

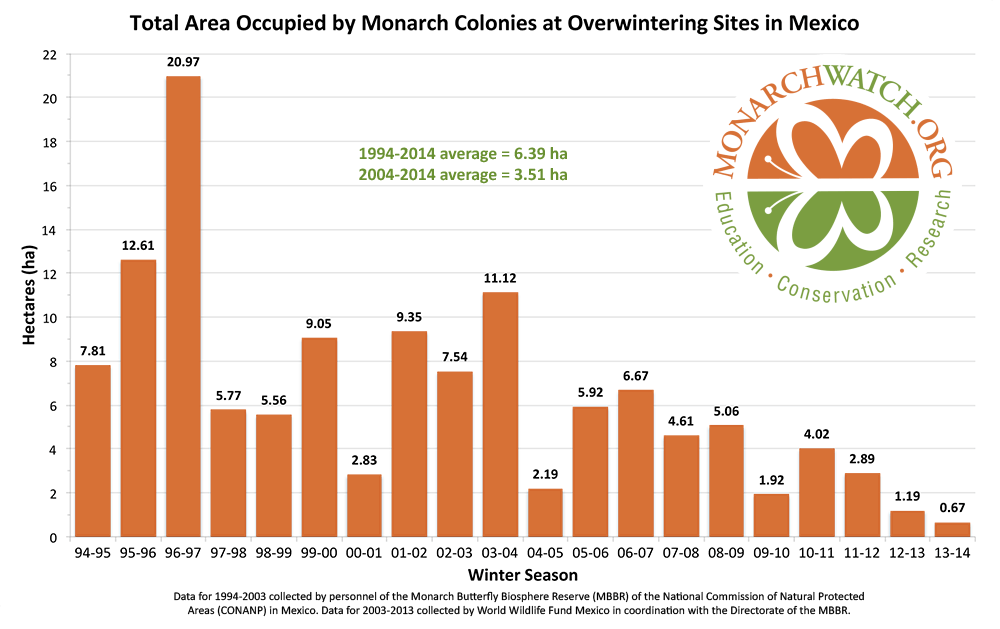

Floating by on their wings of black and orange that resemble panels of stained glass, the monarch butterfly is a favorite sight as summer ends and fall begins. This year, it may be harder to catch a glimpse of these late season butterflies. Over the past decade, their population has declined rapidly due to habitat loss and other environmental factors.

When monarchs arrive, they flock to milkweed plants to sip nectar and lay their eggs. The generation that emerges in NH will face an arduous 3,000-mile journey that takes them from our local fields into the mountains of Mexico.

Monarchs love milkweed, and the reason why is simple: poison. The milky sap found in milkweed leaves is toxic enough to make most animals sick, while monarchs possess a surprising immunity. Because of this a monarch will only deposit their eggs on milkweed leaves. A few days later the very hungry, green-yellow-and-black-striped caterpillar emerges and begins chomping down on the poisonous leaves. Monarchs remain toxic when they emerge as butterflies, and other animals know they will have an upset stomach if they eat one.

The life stages of a monarch are fascinating. On the way to becoming a winged-creature, the caterpillar molts repeatedly before it spins itself a cocoon and undergoes a stunning 10-14 day metamorphosis. Attached to the underside of a plant, the jade green, and gold spotted chrysalis houses the ‘melted’ pupa. The ‘melting’ phenomenon is exclusive to insects, where enzymes break down the body inside a chrysalis, and embryonic-like cells build the butterfly from scratch. The monarch emerges slightly damp, and allows its wings to dry before flying away.

As you catch sight of a monarch and track its winding progress, realize that you are witnessing something that took four to five generations to achieve. Traveling from central Mexico to the southern U.S., and then up the East Coast to New Hampshire, each successive generation completes part of the yearly, multi-generational loop. The monarchs born in NH will travel south to Mexico. Once they arrive in Mexico millions will cluster together and overwinter on the oyamel fir species that grow in an isolated mountain range. Only a fraction of the original oyamel fir forest remains, and it is one of the most endangered ecosystems in Mexico.

Habitat loss in both the United States and Mexico contributes greatly to dwindling monarch populations. The loss of open fields to development, and the steady disappearance of milkweed leave monarchs with limited breeding grounds. Monarchs overwinter in cool, high altitudes on oyamel firs because it provides them with a safe place to enter diapause – a state of lowered energy, but not true hibernation – that allows them to conserve energy. The illegal deforestation of oyamel firs has also contributed to the rapid decline of monarch populations.

Getting Involved

As landowners, we can help the monarch by encouraging milkweed and other species that flower in late summer. In fact, research from Antioch New England shows that mowing milkweed during the beginning and end of July promotes regrowth, and provides more habitat for monarchs to lay eggs and hatch throughout September and October.

Here at ACT, we are managing our Whipple Field Conservation Area next to Polly’s Pancake Parlor in Sugar Hill for plant species beneficial to monarchs and other pollinators.

Planting a butterfly garden full of native wildflowers that provide nectar for pollinators, and gives you the perfect excuse to step outside and see who is arriving.

Taking it a step further, you can track the butterflies and help conservation efforts through Monarch Watch.

Creature Feature: Woodcock's Rite of Spring

It’s known to pull some North Country people out of their homes at dusk, often with favorite libation in hand, to sit and wait, listening intently.

And when they hear the first sign, to cheer and toast the arrival of spring!

What is this event that so fascinates us? The mating display of the woodcock.

While the size of a very plump robin, streaked brown and black to blend in to the forest floor, the American Woodcock (Scolopax miner) is actually a shorebird.

Describing the woodcock’s mating ritual predictably causes a “you’re pulling my leg” response from the uninitiated. (Or, they could just be laughing at us. You know, the folks who think we’re crazy for living up here in the first place.)

But it’s true. For a bird that’s extremely circumspect the rest of the year, they do go a bit crazy this time of year. Maybe like your shy Uncle Charlie hitting the dance floor after a few toasts at your wedding. Who knew?

The woodcock dance goes like this. On his stumpy little legs, the male starts strutting about, bobbing his head, and making a distinctive noise, a loud nasal “peeent!” about every 30 seconds or so, for several minutes. Then he launches himself into the air, gaining altitude and zooming around in wide circles. You can track him by the twittering sounds of the wind vibrating through his outer wingtips. He reaches his apex, then plummets in a corkscrew pattern, all the while emitting warbling and whistling sounds in an ever-increasing pitch. He hits the ground, and then starts all over. Presumably, a female has been judging this display from a modest distance.

Woodcock like early successional forests where there is a good mix of cover and areas where they can probe for food. They also need meadows or fields, or even edges of lawns, where they can perform their mating rituals. At night they will sleep tucked against a tree trunk or beneath a bush where the shelter is good. Tracing back to their shorebird roots, the female hens make indentations in the leaf litter to lay their eggs (clutches of four) much like a plover will along sandy beaches.

If a hen is disturbed early on the risk is high that she’ll abandon the nest. Once the chicks are born, a hen will feign dragging a broken wing along to lure predators away from her brood. Being a plump bird that makes its home on the ground can be risky. Dogs, cats, skunks, raccoons, coyotes, and foxes are all predators of woodcock.

The woodcock’s long bill is specially adapted to rummage for grubs, worms, and insects in the leaf litter and in the ground. They also rock up and down before plunging their bills to extract squiggling worms from the ground. It is believed that their rocking motion creates vibrations that make it easier for them to pinpoint where bugs are hiding.

Woodcock are an important migratory game bird in NH. They are hunted in the fall, and there is a strict bag and time limit as their numbers have been decreasing for years across the northeast, most likely due to habitat loss. NH Fish & Game has offered cost sharing to landowners who improve habitat for woodcock. Several years ago, ACT took advantage of this to hire a brontosaurus – a cutting head mounted on excavator body – to chop through an area that had gotten too dense for the ground dwelling birds. Now, the young alders that woodcock particularly like are growing again. And we’re hearing several of the birds peenting and doing their dance every evening at dusk.

Creature Feature: The Buzz About Bees

Step outside into your vegetable patch or flower garden this time of year and you’ll hopefully see honeybees or bumblebees buzzing about. Bees are one of the reasons we can eat fresh fruits and vegetables, and they play an essential part of our food system. In the United States alone, bees provide pollination services valued at billions of dollars. Blueberries, strawberries, apples, pumpkins, and many other local crops depend on these species.

With over 20,000 species of bees worldwide, and an estimated 250 species in NH, bees are among the most important pollinators on earth. Think “pollinator” and the honeybee (Apis mellifera) may be the first thing that comes to mind. A multitude of species including bumblebees, carpenter bees, and honey bees and bumblebees help pollinate crops in our local farms. Over the past decade pollinators, and bees in particular, have been disappearing at a worrisome rate.

Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) strikes fear into the heart of every beekeeper. Go to bed one night and your bees are fine, wake up the next morning and all of your adults bees are suddenly dead or have disappeared, leaving behind a lone queen.

Biologists are still unsure why CCD happens, however research points to stressors including pesticide use, habitat loss, and harmful pathogens. Hit with a single stressor, a hive can usually rebound. When a colony is faced with a combination of them, they are often unable to survive.

Sit for a while in your garden, and you may see a variety of bumblebees, like the tri-colored bumblebee (Bombus ternarius), American bumblebee (Bombus pensylvanicus), and common eastern bumblebee (Bombus impatiens). Often overlooked, are solitary carpenter bees, mason bees and sweat bees that are all found in our region of NH.

Both social and solitary bees live in NH. At the heart of every social bee colony is a queen bee who ensures the continuation of her hive. Honeybees are social, building organized honeycomb nests and a single colony may include thousands of workers and drones. Solitary bees, like the mason and sweat bees live by themselves and prefer nesting in sandy ground or even decaying logs. Bumblebee colonies are smaller, ranging from 50-400 bees and also tend to form nests in the ground.

With honeybee colonies dying off and disappearing across the country, scientists have been studying hives to see what stressors are weakening or killing bees. Documented stressors include pesticides, harmful pathogens, and pests such as hive beetles that can wreak havoc in colonies. Loss of land that was once home to wildflowers, either to development or to row crops – and the pesticides that many farmers use – has also hurt bees, as they are forced to fly longer distances for subpar pollen and nectar yields.

Here in the North Country where winters can last for six months, it’s especially tough on our bees. During the winter honeybees surround their queen forming a dense warm ball to keep her alive until spring. Bees eat their honey stores during the winter, but if a freezing winter drags on and reserves are drained before spring the colony’s survival becomes tenuous.

NH’s bees face many challenges as they pollinate our vegetables, fruits, and flowers year after year. The next time you’re harvesting vegetables for dinner, or picking up your CSA share consider for a moment the small, but mighty pollinator that made it all possible. From CCD to frigid winters, and creeping habitat loss it may seem the deck is stacked against bees, but the good news is there are steps you can take to help.

What can you do to attract honeybees and bumblebees to your own backyard?

1.) Start a native wildflower garden, and plant it so your have a diversity of flowers that bloom at different times throughout the summer. This gives bees a reliable foraging ground and provides them with excellent pollen and nectar diversity. The Pollinator Partnership nonprofit provides an extensive wildflower plant guide with flowering times for New England.

2.) If you use pesticides or insecticides consider eliminating them entirely, or only applying them in the late afternoon when bees are less likely to go on pollen runs. Bees are gentle creatures, unlikely to sting unless provoked. Think of all the beautiful flowers and vegetables you and your neighbors are able to enjoy because of their presence.

3.) Get information from credible sources, like The Pollinator Partnership, Xerces Society, The Bee Informed Partnership, and UNH Cooperative Extension.

Creature Feature: Our Common but Elusive Owl

Who cooks for you? Who cooks for youuuaallll?

You can hear the unmistakable call of the barred owl throughout the year, but they really get revved up in late winter as their mating season begins.

Barred owls are big and chunky.

Barred Owls

NH’s most common owl, the barred owl (Strix varia) sports horizontal bars running across its chest, vertical stripes down its belly, and a smooth round head – no”ears”or tufts.

In addition to the familiar “Who cooks for you?”

call, barred owls engage in rather dramatic caterwauling during their courtship, which begins in February. Breeding starts in March and goes through the summer.

Barred owls tend toward monogomy. They like to nest in cavities in snags (large dead trees) within dense forests. Here at ACT we manage our land to keep and sometimes even create such trees for owls and other wildlife.

Two to four eggs are laid per clutch, and the female incubates the eggs for four weeks before they hatch. After another six weeks, most young successfully fledge. This venturing forth from the nest coincides with the emergence of the young and not so young of owls’ favorite foods, such as red squirrels, mice, voles, mink, and even rabbits or skunks. The oldest barred owl on record was 24 years old.

At about six weeks old, the young are ready to venture forth into the world on their own, and fledge. This coincides with the natural increase in populations of owls’ favorite prey, including red squirrels, mice, voles, mink, and even young hares, skunks, and other birds. Barred owls may even catch crayfish near the water’s edge.

We all grew up with the image of the “wise old owl.” Their steady, impenetrable gaze certainly gives the impression of deep thought. Biomechanically, owls are remarkable. A lot of the magic happens from their neck up. Imagine their heads as dish antennas that are specially engineered to let them hear and see where their prey may be lurking.

Their head feathers are arranged to magnify sounds, so they can easily hear the smallest prey rustling about. The extremely photosensitive eyes that give them excellent night vision take up half their skull. Because these huge eyes are actually tube shaped, owls can’t roll their eyes – instead they can swivel their necks an astounding 270-degrees. They lock their eyes on sounds of would-be prey. Then with speed and silence they swoop down to grab it. This winter, look carefully in the woods and open fields where there are rodent tracks, and you may well find the imprint of owl wings in the snow.

The barred owl is ranked as a species of “least concern” in NH, meaning the population is steady. They are a very adaptable species, but their greatest threat is the loss of forested landscapes and the open marshland where they like to hunt and nest.

Here’s a link to a live webcam of a Great Horned Owl nest with chicks in Georgia. Though uncommon up here (you’re more likely to find them in southern NH), the great horned is actually a predator of the barred owl.

The barred owl is a magnificent creature, and because they are non-migratory and maintain a territory, your chances of spotting one is quite good.

Creature Feature: Mad as a March Hare?

Remember the March Hare and his pal the Hatter in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland?

Both were a bit crazed or mad as the Cheshire Cat said. The hatter, we may surmise, from mercury poisoning (used in felt making for hats) and the Hare, well, blame it on March.

Hares are normally shy and timid creatures. But suddenly, come March and their breeding season, they'll be out boxing other hares, hopping about quite heedlessly looking for their true loves, and thumping the ground just because. In other words, acting a bit mad.

March Hare and Hatter stuffing Door Mouse into a teapot.

The snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) is common in the North Country, particularly in brushy areas and forest edges. Usually not easily seen, they are experts at concealment and often freeze at the approach of a person or predator.

Ecologists use the term crypsis for the ability of an organism to avoid detection. The hare's cryptic strategy is chromatic: its fur changes color in response to the environment. As daylight decreases, its coat becomes the color of snow for winter.

As daylight increases toward spring, its coat becomes a forest-floor reddish-brown.Year-round, snowshoe hares have coal-black eyes. In snow, you may spot a hare motionless beneath a small evergreen when the snow weighs its boughs down like a little tent. Just look for those black eyes.

The best telltale for hares are the tracks. The toes on their large, furry feet open wide like snowshoes as they bound along. Their big feet keep them buoyant in the snow, and their powerful haunches can propel them an impressive 27 mph on a high speed getaway from the jaws of lynx, bobcats, coyotes, and dogs.

And yes, hares do breed prolifically. From March until August it is open season for breeding and a female can have 2-3 litters per year of 3-5 leverets (baby hares). For hares it is possible to be 'mad as a March hare' for six months of the year.