Floating by on their wings of black and orange that resemble panels of stained glass, the monarch butterfly is a favorite sight as summer ends and fall begins. This year, it may be harder to catch a glimpse of these late season butterflies. Over the past decade, their population has declined rapidly due to habitat loss and other environmental factors.

When monarchs arrive, they flock to milkweed plants to sip nectar and lay their eggs. The generation that emerges in NH will face an arduous 3,000-mile journey that takes them from our local fields into the mountains of Mexico.

Monarchs love milkweed, and the reason why is simple: poison. The milky sap found in milkweed leaves is toxic enough to make most animals sick, while monarchs possess a surprising immunity. Because of this a monarch will only deposit their eggs on milkweed leaves. A few days later the very hungry, green-yellow-and-black-striped caterpillar emerges and begins chomping down on the poisonous leaves. Monarchs remain toxic when they emerge as butterflies, and other animals know they will have an upset stomach if they eat one.

The life stages of a monarch are fascinating. On the way to becoming a winged-creature, the caterpillar molts repeatedly before it spins itself a cocoon and undergoes a stunning 10-14 day metamorphosis. Attached to the underside of a plant, the jade green, and gold spotted chrysalis houses the ‘melted’ pupa. The ‘melting’ phenomenon is exclusive to insects, where enzymes break down the body inside a chrysalis, and embryonic-like cells build the butterfly from scratch. The monarch emerges slightly damp, and allows its wings to dry before flying away.

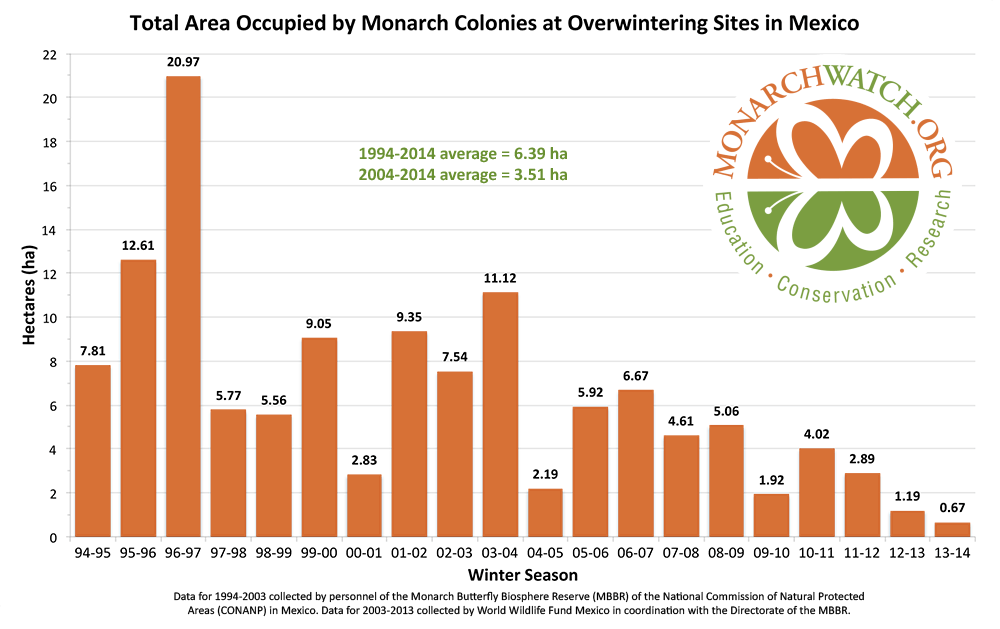

As you catch sight of a monarch and track its winding progress, realize that you are witnessing something that took four to five generations to achieve. Traveling from central Mexico to the southern U.S., and then up the East Coast to New Hampshire, each successive generation completes part of the yearly, multi-generational loop. The monarchs born in NH will travel south to Mexico. Once they arrive in Mexico millions will cluster together and overwinter on the oyamel fir species that grow in an isolated mountain range. Only a fraction of the original oyamel fir forest remains, and it is one of the most endangered ecosystems in Mexico.

Habitat loss in both the United States and Mexico contributes greatly to dwindling monarch populations. The loss of open fields to development, and the steady disappearance of milkweed leave monarchs with limited breeding grounds. Monarchs overwinter in cool, high altitudes on oyamel firs because it provides them with a safe place to enter diapause – a state of lowered energy, but not true hibernation – that allows them to conserve energy. The illegal deforestation of oyamel firs has also contributed to the rapid decline of monarch populations.

Getting Involved

As landowners, we can help the monarch by encouraging milkweed and other species that flower in late summer. In fact, research from Antioch New England shows that mowing milkweed during the beginning and end of July promotes regrowth, and provides more habitat for monarchs to lay eggs and hatch throughout September and October.

Here at ACT, we are managing our Whipple Field Conservation Area next to Polly’s Pancake Parlor in Sugar Hill for plant species beneficial to monarchs and other pollinators.

Planting a butterfly garden full of native wildflowers that provide nectar for pollinators, and gives you the perfect excuse to step outside and see who is arriving.

Taking it a step further, you can track the butterflies and help conservation efforts through Monarch Watch.